The 12 Days of Safety Myths

December 17, 2018

By Don Kostelec

“Just go to the nearest crosswalk.”

Seems simple enough, eh? Pedestrians, just go to the nearest crosswalk and cross there.

How many times have you heard that from a traffic safety campaign or a law enforcement agency? It’s as if they all have a NHTSA app to give them a pedestrian safety catch phrase of the day.

A Boise man was killed in July 2018 at an unmarked crosswalk a few hundred yards west of here. The police insinuated he should have instead used this “crosswalk” at the nearest controlled intersection. The re-striping of the crosswalk has been ignored for years by ITD.

If you quiz highway agencies or law enforcement on it their response is usually “We’re just reminding people of the law.”

True. But these agencies never bother to look at the law in a historical context. They never examine how traffic engineers have designed roads to take advantage of their understanding of this law to promote greater dominance of motorists on the streets. They never account for the value of the pedestrian’s time despite spending millions on corridor studies to do value of time analyses for motorists. From my experience, most of the agency personnel spouting these messages really mean to go to the nearest signalized (or controlled) crosswalk.

One of my favorite TV news personalities is Stanley Roberts. He worked for a long time in San Francisco doing spots called “People Behaving Badly,” where he routinely chronicles motorists failing to yield to pedestrians in crosswalks, especially unmarked ones. He recently moved to Phoenix where it appears he’s having a blast.

A December 13, 2018 piece by Roberts was posted on AZFamily.com. His lede is:

- “In Arizona, sometimes the nearest crosswalk can be a quarter mile away, which begs the question: Does the state or city really expect someone to walk a quarter mile or more just to legally cross the street?”

History

The prevailing laws on crosswalk use in the United States emerged in the 1920s and 1930s as motordom began its vicious public relations campaign to clear the way for automobiles to dominate the streets. They created campaigns using term “jaywalking” (a “jay” being a hick or a rube who didn’t know how to cross streets among an abundance of cars) and related laws as a way to publicly shame pedestrians for not crossing the streets the way they had done for centuries.

After all, there was a new kid on the block–the automobile–and they were determined to establish its dominance over the streets. They enlisted a new profession called “traffic engineers” to do part of the deed for them, all in the name of efficiency. This history of motordom taking control of the streets and relegated people who walk to second class road users is well-chronicled in Peter Norton’s book Fighting Traffic.

These efforts, which Norton headlined as “Organized Ridicule,” can be summed up what Norton summarizes from the Automobile Club of Southern California: It is not particularly difficult to sell pedestrian control to a population which is motor-minded.

The laws put in place to force pedestrians to make more orderly crossings of the street led to the definition of the crosswalk, which is generally defined as any street corner or intersection. Today, those crosswalks are either marked (include some type of striping across the road) or unmarked (an assumed crosswalk that exists at every intersection and across every leg at that intersection. By law, pedestrians have the same right-of-way in a marked and unmarked crosswalk.

Additional laws to regulate pedestrians at traffic signals became more prevalent as that technology was deployed. Cross only when your parallel vehicle movement has the green. Pedestrian-specific signals emerged much later and gave pedestrians the WALK, flashing DON’T WALK, and solid DON’T WALK signals we’re all familiar with today.

Putting it in 1930s Street Context

Let’s strip away from the overt campaigning by motordom for a second and consider what the command of “just go to the nearest crosswalk” meant when walking about cities of the 1920s and 1930s. In researching the onset of these laws where I live in Idaho, we found that cities were adopting pedestrian-related ordinances in this timeframe; the State of Idaho didn’t follow with state laws until the 1950s.

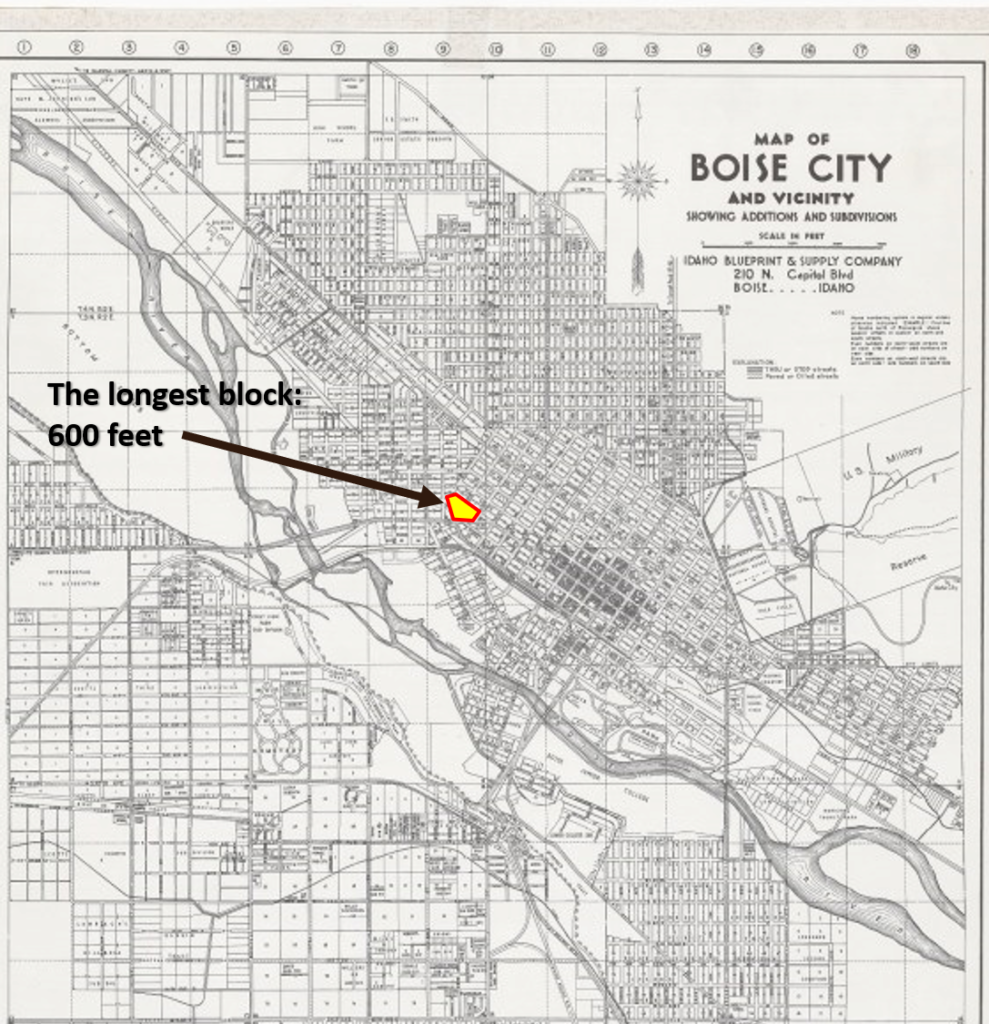

I located a map of the City of Boise from the early 1940s through the River Street Digital History Project, which would be from the approximate time the laws requiring pedestrians to cross at crosswalks were adopted.

In scanning the high resolution version I was seeking what the longest block length was in Boise at this time. It’s 600 feet long, near the intersection of Fairview Avenue and 22nd Street. There’s a hotel on the site today. If a pedestrian came out of a building at the mid-block it would mean a 300-foot walk in either direction to get to a crosswalk, or 85 seconds. Most blocks in Boise’s city limits at this time were 300 to 350 feet, meaning a 45-second walk from a mid-block location to the nearest corner. To me, those aren’t unreasonable expectations placed upon a person who is walking.

The longest block in Boise in the early 1940s was 600-feet long.

Image: River Street Digital History Project.

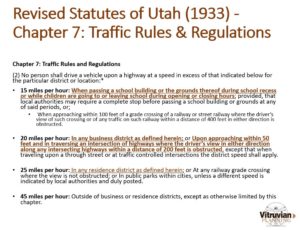

The street context at the time was also notably different than today. Vehicle speeds were not as high. In researching Utah law, I found that land use dictated speed limits in Utah’s Traffic Rules and Regulations, 1933. Essentially, no roadway had a speed limit above 25 mph within residential or business districts (almost an entire city, not counting industrial areas).

Utah traffic code, 1930s.

Speed limits based on land use! Imagine that.

Pulling it all together: Pedestrians didn’t have to walk that far to find a crosswalk to use in the cities of the 1930s. They weren’t exposed to high vehicle speeds like today. There weren’t as many travel lanes at the time since traffic volumes were low.

Today’s Street Context

Traffic engineers are guilty of taking advantage of these laws and driving the misguided message common to their own agency’s traffic safety campaigns. They clearly interpret “just go to the nearest crosswalk” to mean the nearest controlled crosswalk. They hate designing frequent controlled crossings for pedestrians because it might mess up the precious traffic flow that they’ve been seeking ever since the creation of their profession.

ITD signs erected along Glenwood are intended to force pedestrians to the nearest controlled intersection. There is a 3,700-foot gap between the two controlled intersections on this stretch.

Just four miles west of that Fairview and 22nd Street intersection in Boise is a section of State Highway 44 (or Glenwood Avenue) that has a series of signs (image at right) intent on restricting pedestrians from crossing except at controlled intersections.

(Aside: I’m 100% certain the engineers at the Idaho Transportation Department who approved these signs don’t understand the definition of an unmarked crosswalk. There are two “public” streets that access Glenwood on the east side between the controlled intersections of Chinden Boulevard and Marigold. They are public streets managed by Ada County as part of their fairgrounds complex.)

If a pedestrian dutifully followed the directions as dictated by the Idaho Transportation Department they would find there is a 3,700-foot gap between signalized intersections at Chinden Boulevard on the south and Marigold Avenue on the north. That’s 500 seconds of walking time (!!!!!!) for a pedestrian who comes out mid-block in this stretch hoping to cross the street.

If we accounted for pedestrian delay the same way agencies like ITD account for vehicle delay, the equivalent to forcing a pedestrian to the nearest controlled intersection in this situation is like forcing a motorist to drive five miles up the road to make a u-turn just to cross the street. Can you imagine the outcry if they exerted that much control over motorist access on a surface street? Yet, it’s perfectly acceptable for them to do this to pedestrians.

Pedestrians: Design Guidance is on Your Side!

Here’s the dirty secret the traffic engineers don’t want you to know:

Ho, ho, ho! Santa AASHTO supports controlled pedestrian crossings at frequent intervals!

- AASHTO and the Institute for Transportation Engineers (ITE) support pedestrians having more opportunities to cross a street.

The AASHTO Guide for the Planning, Design, and Operations of Pedestrian Facilities might be your greatest gift from Santa. Chapter 3 on Pedestrian Facility Design includes a section on “Marked Crosswalks” (page 81; emphasis added):

- “Assumptions–Assume that pedestrians want and need safe access to all destinations that are accessible to motorists…

- “Frequency–Pedestrian must be able to cross streets and highways at regular intervals. Unlike motor vehicles, pedestrians cannot be expected to go a quarter mile or more out of their way to take advantage of a controlled intersection.”

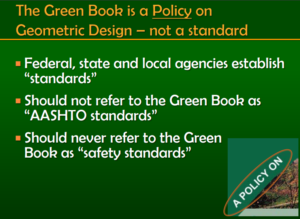

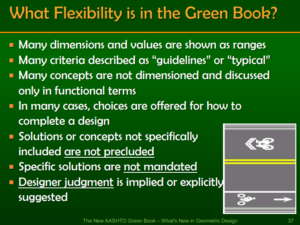

In the 6th Day of Safety Myths I covered the AASHTO Green Book and how it’s seen as the predominant guidance for engineers. The Green Book references the AASHTO Guide for the Planning, Design, and Operations of Pedestrian Facilities at least 30 times in its more than 1,000 pages. So, AASHTO clearly see this specific guidance document on pedestrians as valid guidance for those using the Green Book.

The Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE), a much more enlightened group of engineers than those who develop AASHTO guidance, take the need for more frequent pedestrian crossings a step beyond AASHTO. ITE’s Designing Walkable Urban Thoroughfares: A Context Sensitive Approach has the following language:

- “Pedestrian facilities should be spaced so block lengths in less dense areas (suburban or general urban) do not exceed 600 feet (preferably 200 to 400 feet) and relatively direct routes are available.” (page 32)

- “In the densest urban areas (urban centers and urban cores), block length should not exceed 400 feet (preferably 200 to 300 feet) to support higher densities and pedestrian activity.

- “Generally, however, consider providing a marked midblock crossing when protected intersection crossings are spaced greater than 400 feet or so that crosswalks are located no greater than 200 to 300 feet apart in high pedestrian volume locations, and meet the criteria below.” (page 153)

The Last Hurdle: MUTCD and Liability

There you have it! The two leading transportation engineering organizations in the United States support greater density in pedestrian crossings. What’s the problem with your local traffic engineers?

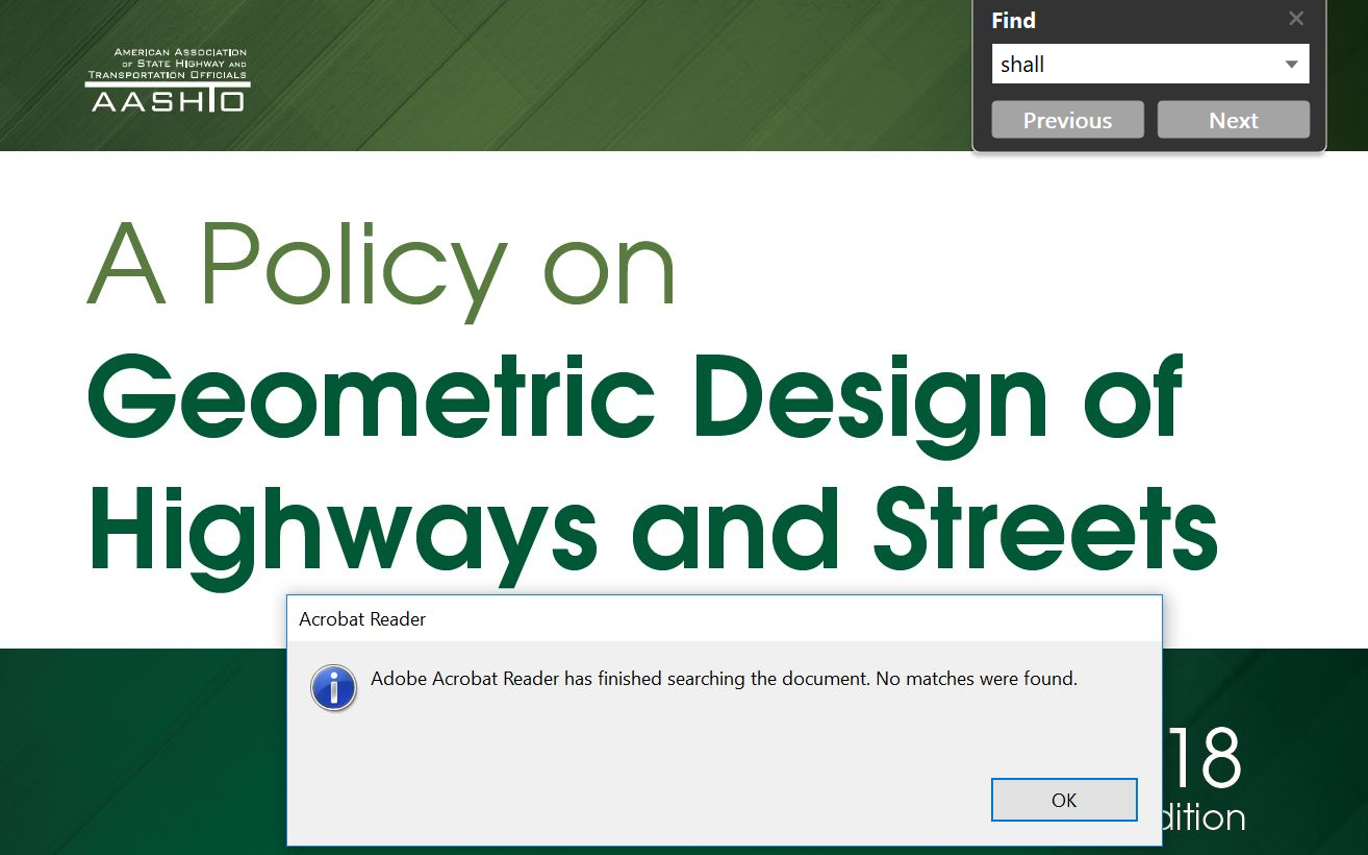

That’s where it gets sticky and slightly harder to overcome their stubbornness. The Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD), unlike the AASHTO Green Book, has several elements that are truly deemed “standards,” or compulsory elements. The word “shall” is used in many instances in the MUTCD, including the section on signal warrants contained in Section 4C of MUTCD:

- “An engineering study of traffic conditions, pedestrian characteristics, and physical characteristics of the location shall be performed to determine whether installation of a traffic control signal is justified at a particular location.”

Section 4C.05 Warrant 4, Pedestrian Volume, includes “shall” statements related to pedestrian volumes.

While an engineer’s concerns over liability in approving such a crossing in the absence of these values is valid on the surface, they still have the flexibility of their own engineering judgment to approve crossings in the absence of these warrants being met. Part 1A of MUTCD states:

- “Thus, while this Manual provides Standards, Guidance, and Options for design and applications of traffic control devices, this Manual should not be considered a substitute for engineering judgment. Engineering judgment should be exercised in the selection and application of traffic control devices, as well as in the location and design of roads and streets that the devices complement.”

In my work with engineers who have a modern perspective, they tend to take their duty of engineering judgment seriously. They don’t flippantly approve more frequent pedestrian crossings, but they do take into account factors such as land use, gaps between crossings, and presence of things like schools, parks, senior center, transit stops, and shopping areas.

It was drilled into my head as a young project designer who was managing engineering projects alongside a licensed engineer that we must document the times in which we used engineering judgment to deviate from the things like the “shall” statements of MUTCD. We were to put a memo in the project file explaining how we reached that decision and the engineer of record was to sign them.

This procedure is affirmed in in the National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) Legal Research Digest #63: EFFECT OF MUTCD ON TORT LIABILITY OF GOVERNMENT

TRANSPORTATION AGENCIES, specifically page 25: “MUTCD is not a substitute for engineering judgment.”

NCHRP’s Legal Research Digest #57 TORT LIABILITY DEFENSE PRACTICES FOR DESIGN FLEXIBILITY notes on page 13: “The MUTCD and other references are guidelines, not cookbooks.”