The 12 Days of Safety Myths

December 14, 2018

by Don Kostelec

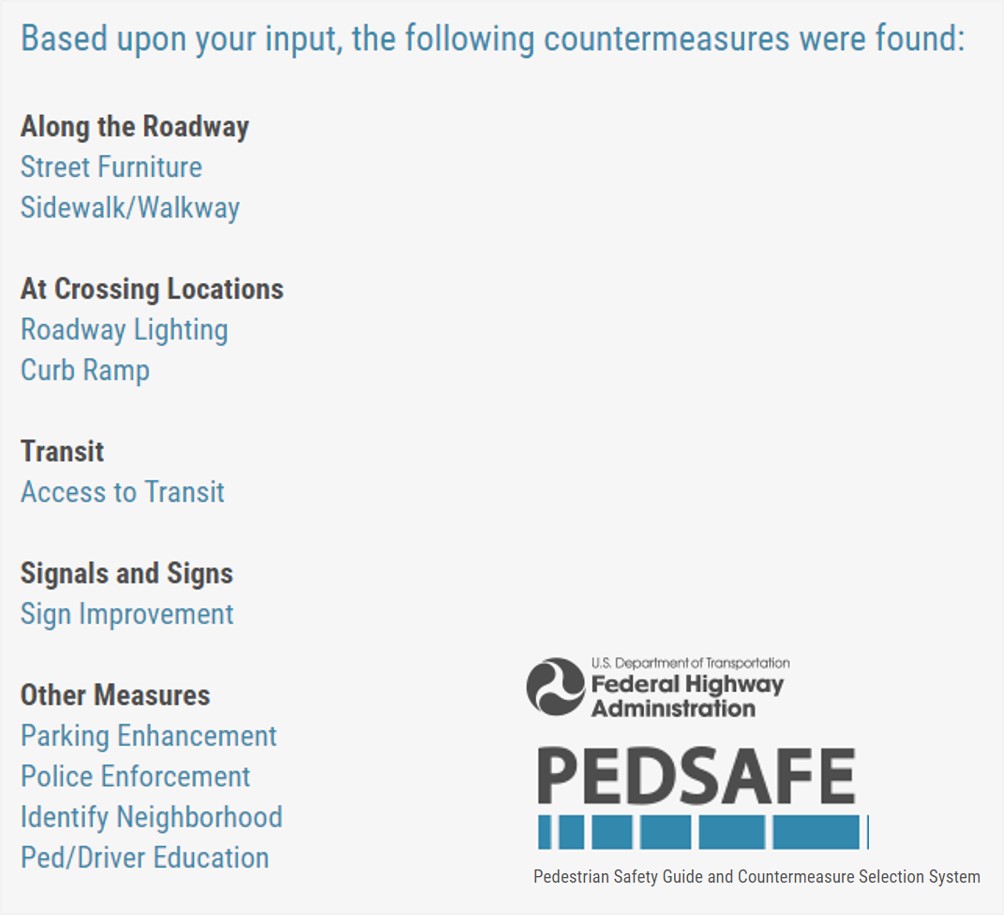

Walk Farce called it the ultimate “go home, traffic engineers, you’re drunk!” study and survey. It’s a research project funded by the National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) called “Guide for Pedestrian and Bicycle Safety at Alternative Intersections and Interchanges (A.I.I.).”

“Alternative intersections” is putting it nicely for engineers who are sipping a little too much spiked eggnog these days. Here’s a more detailed description of this ongoing research:

- “New alternative intersection and interchange designs – including Diverging Diamond Interchanges (DDI), Displaced Left-Turn (DLT) or Continuous Flow Intersections (CFI), Restricted Crossing U-Turn (RCUT) intersections, Median U-Turn (MUT) intersections, Quadrant Roadway (QR) intersections – are being built in the United States. (P)edestrian paths and bicycle facilities may cross through islands or take different routes than expected. These new designs are likely to require additional information for drivers, cyclists, and pedestrians as well as better accommodations for pedestrians and bicyclists, including pedestrians with disabilities.”

Search YouTube for any of those intersection types an you’re likely to find a treasure trove of DOT porn explaining the virtues of these intersections for maximize traffic flow. All of these designs require navigation by pedestrians (and bicyclists in some situations) in what traffic engineers call “stages”. A two-stage crossing, for example, is something we’re all familiar width. It’s essentially a median or refuge island at a street crossing. Crossing to the next island is a stage.

I don’t dispute the safety benefit that refuge islands provide, especially at mid-block crossings containing Rectangular Rapid Flashing Beacons or Pedestrian Hybrid Beacons (formerly HAWK signals). Allowing a pedestrian to navigate a mid-block crossing in two stages allow them to negotiate each direction of traffic separately and the traffic controls are exclusively regulated by the pedestrian.

The problem comes into play at traditional signalized intersections where the introduction of two-stage, three-stage and four-stage crossings have become commonplace. Be aware at a public meeting when a traffic engineers starts spouting the virtues of requiring pedestrians to do multi-stage crossing. It’s like the Wise Man who was carrying the myrrh: “Oh…gee…thanks. Can you find out where the other dude got the gold and bring me some of that?”

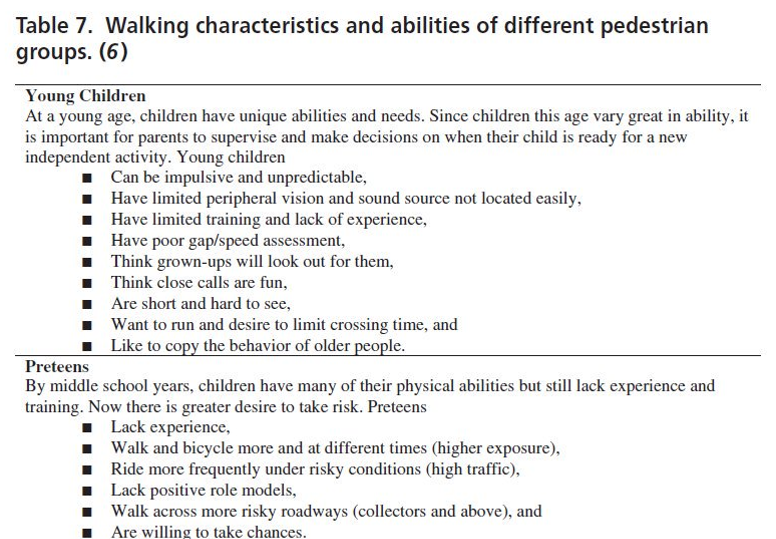

While islands do break the visual field of the intersection and allow pedestrians to navigate across one vehicular traffic movement at time, traffic engineers routinely use them to increase pedestrian delay, especially for disabled people, older adults, and young children that have walk speeds slower than the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) minimum rate of 3.5 feet per second that is used to time pedestrian signals.

Two-Stage Pedestrian Crossing Schematic from FHWA

The Federal Highway Administration, in its guidance for signalized intersections, chose some interesting language to admit that two-stage crossings discriminate against those who cross at a slower pace.

- “Potential Benefits: Medians of moderate width can allow pedestrians to cross in one or two stages, depending on ability.” (Marxist much?)

The schematic drawing shows “Separate pedestrian phases,” which means they likely don’t want to give a lot of green signal time to the parallel street crossing (typically called the minor street), so they don’t give pedestrians enough time to cross in one signal phase. This maximizes vehicle throughput for the “major street” (the four-lane road in this drawing).

“Hey, granny, you don’t walk fast enough to meet our goals for vehicle throughput, so we’ll stick you in the middle for another 3 minutes. Deal with it.” That’s when she got run over by the reindeer.

This video shows a person feeling they must run across the intersection because the traffic engineers viewed the two-stage crossing as more of an opportunity to limit cycle lengths for side street than to provide refuge for people. I captured it in Pleasant Hill, Iowa, along a highway managed by Iowa DOT.

Behold, the 5-Stage Crossing!

That brings us to the spiked eggnog part of this. The NCHRP study is looking at intersection concepts that make two-stage crossings look like a piece of fruitcake. Take three minutes to watch this video and you’ll understand. Hit the sauce while you’re at it.

This shows how the traffic engineering profession has reached a new level of absurdity. Much of the language in the actual survey (link now dead) framed five-stage crossings as some type of virtue for people who walk. A five-stage crossing is just an antiseptic for engineers to tell pedestrians “Prepare to wait even longer at our already-absurd intersections.”

If we are at a point where 5-stage crossings are consider an option, then that means we need to start to show DOTs they must move toward over/underpasses that provide the ultimate protection while not creating excessive delay (Las Vegas Boulevard-style pedestrian overpasses or some Dutch-style treatments). I’m normally opposed to pedestrian overpasses, but the reason those along Las Vegas Boulevard aren’t as punitive to pedestrian crossing distance and time compared to traditional pedestrian overpasses is they have escalators, stairs, and elevators, rather than a maze of ramps. The result is the time for pedestrians to cross is minimized and may actually be shorter than them having to wait through a traditional traffic signal cycle.

If they can spend the massive amounts of money to build these intersections, then spending a bit more so pedestrians and bicyclists don’t have to navigate a car-centric hellscape seems within reason if the engineers studying and designing these truly care about safety.

The engineers look at safety at these intersection through the lens of reducing conflict points between motorists and pedestrians. That’s definitely a valid point when compared to a conventional 7-lane by 7-lane intersection.

Pedestrian Level of Service and Value of Time

The problem is they fail to consider the value of a pedestrian’s time. Which is funny, because they love to talk about how many seconds they shave off a commute and use that compute a “value of time saved” dollar figure to woo elected officials and the public into spending billions on these crazy designs.

In failing to consider a pedestrian’s time, they’ve also failed to consider FHWA’s own published guidance related to pedestrian delay and safety.

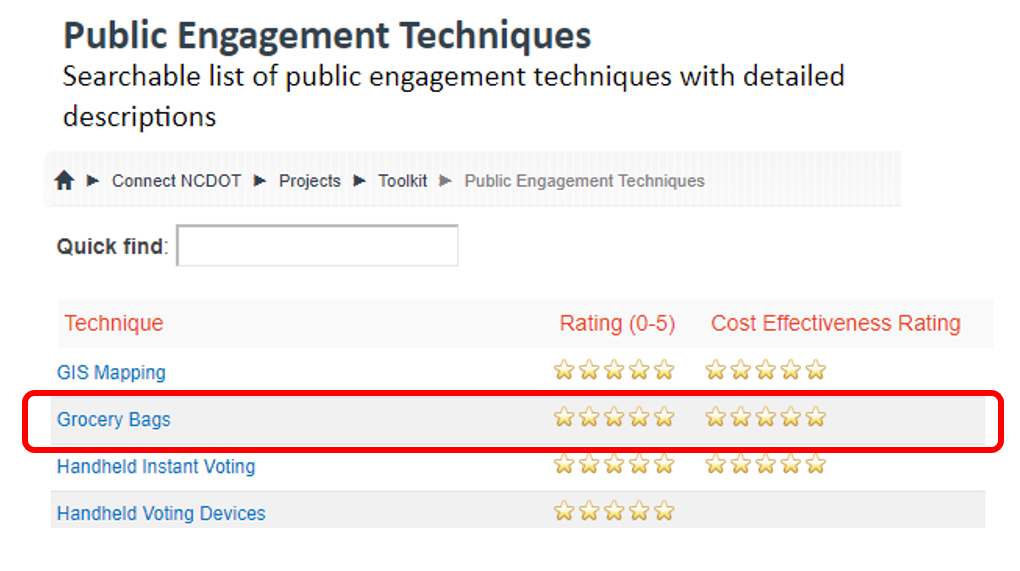

If you’ve ever been involved in public meetings or on steering committees with traffic engineers you’ll hear merrily caroling about vehicle level of service. Use the phrase “pedestrian level of service” with your local traffic engineer and you’re likely to get a confused puppy dog head tilt.

The same folks at FHWA who developed the guidance for vehicle level of service also have a series of guidelines for pedestrian and bicyclist level of service. The module to run pedestrian or bicyclist level of service is in the exact same software packages they use to run vehicle level of service analysis.

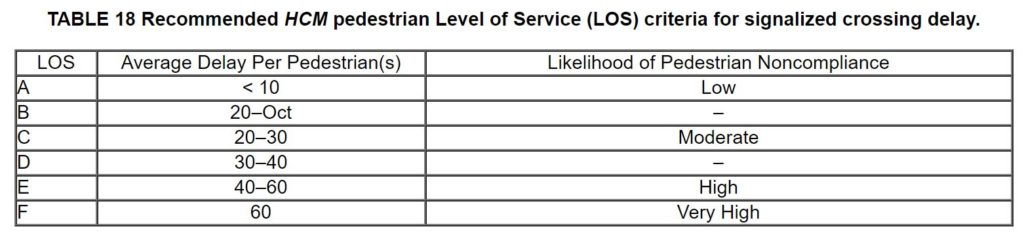

For purposes of multi-stage pedestrian crossings FHWA looks at pedestrian level of service through the lens of average delay experienced by a pedestrian when waiting to cross. They cite research that found that “safety–motivated pedestrian control signals at signalized intersections may actually reduce safety by encouraging noncompliance to avoid the ‘largely unnecessary delay imposed’ on pedestrians.”

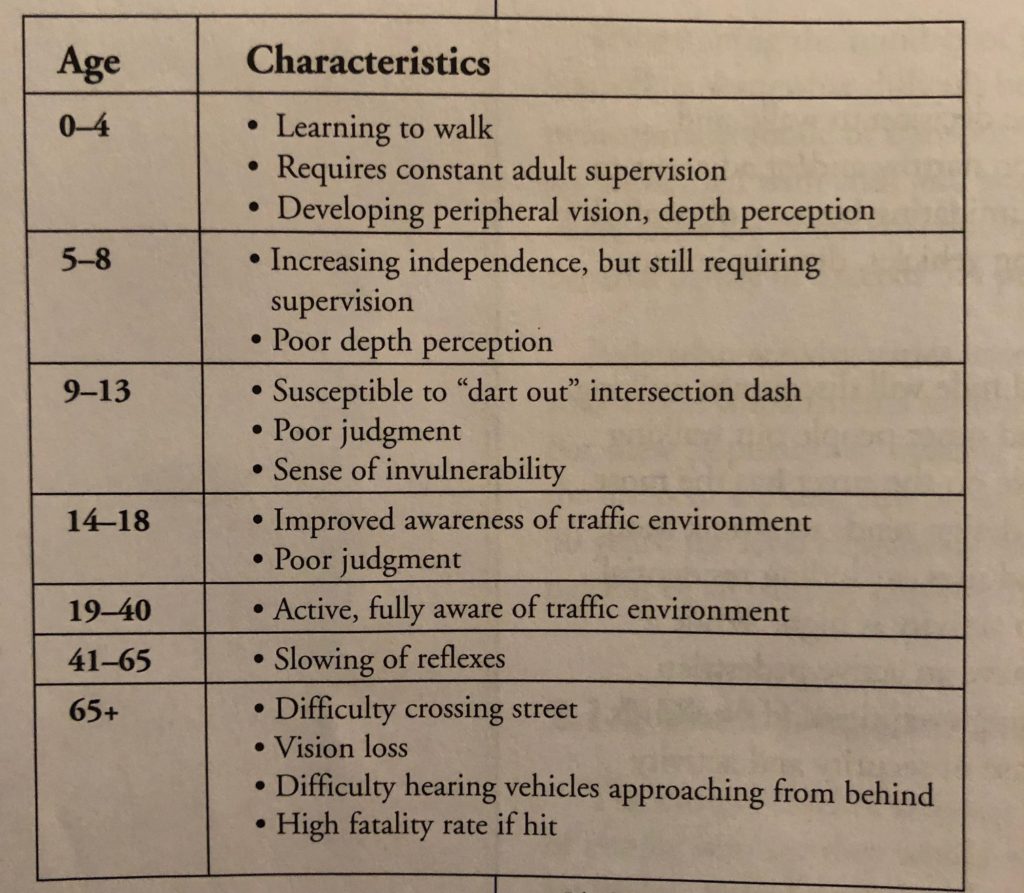

The table below shows different levels of service based on average pedestrian delay at the intersection. Average delay means the average time it takes a pedestrian to get a walk signal once arriving at the intersection. The right column is important as the studies found that longer pedestrian wait times, especially those longer than 40 seconds, leads to high or very high pedestrian noncompliance. This means pedestrians may ignore the WALK signal, or may attempt to shoot a gap in traffic, or may choose to cross elsewhere along the corridor but not at an intersection. Think about how many times you’ve waited more than two or three minutes to cross an intersection. That means the engineers forced pedestrian level of service “F” on you, a level of service “F” that many engineers would refer to as “failing” when vehicle traffic was measured through that same lens.

Pedestrian Level of Service as a function of average delay.

(Aside: One of my favorite lines in this pedestrian level of service section by FHWA is this one: “Indeed, despite the legal precedence of pedestrians over vehicles in the crosswalk, Virkler found that vehicles occasionally occupy a portion of the crosswalk during the pedestrian phase.” Thanks, Sherlock!)

Now think back to the five-stage crossing shown in that video. There’s a strong likelihood that, if implemented, the traffic signal cycle lengths will leave a pedestrian stranded in two or three of those islands to wait through another cycle length. Earlier in my career I looked more closely at one of these crossings of a Median U-turn (MUT) street in Chapel Hill, NC and found the average time to cross was more than three minutes, including nearly two minutes stranded in the median flanked by loud, high speed traffic.

I’ll reserve judgment on the research itself until it’s published. I know some of the people working on the project. They’re good people and solid researchers. I sent them a lengthy set of comments that are consistent with this post. We’ll see what happens.

My fear is they’re co-opted by the notion that since DOTs are already building these absurd intersections we need put as much lipstick on the pig as possible. Instead, let’s hit the reset button, truly account for pedestrian-related science on these matters, and realize once we reach this level of absurdity in intersection design we must fully separate pedestrians and bicyclists in meaningful ways.

Previous Posts in the 12 Days of Safety Myths Series:

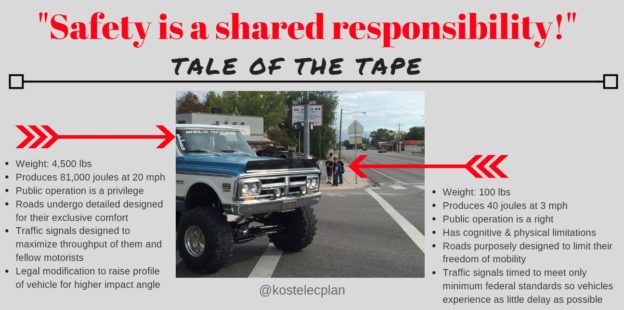

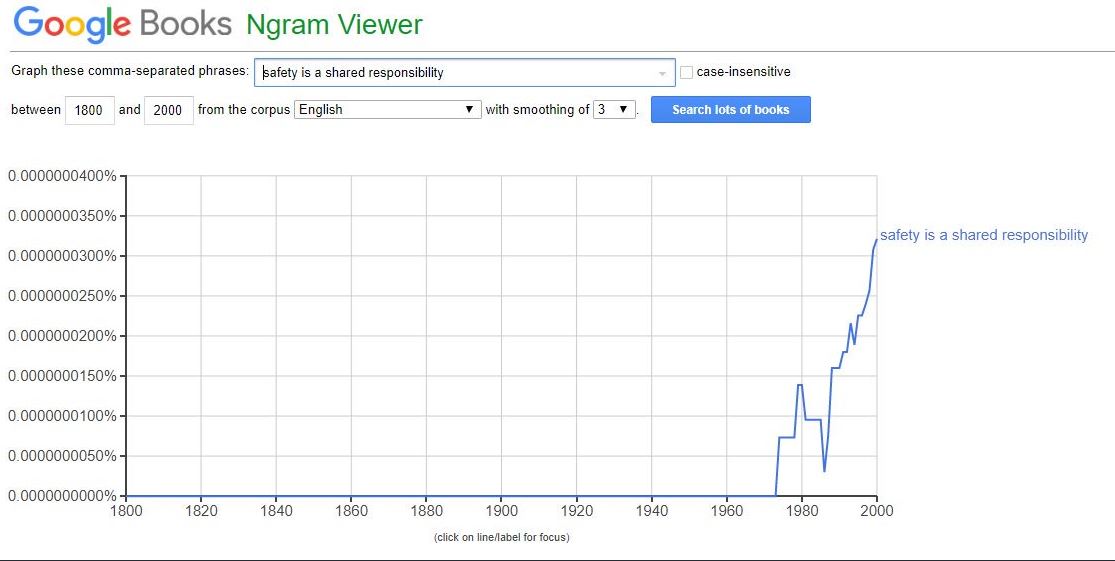

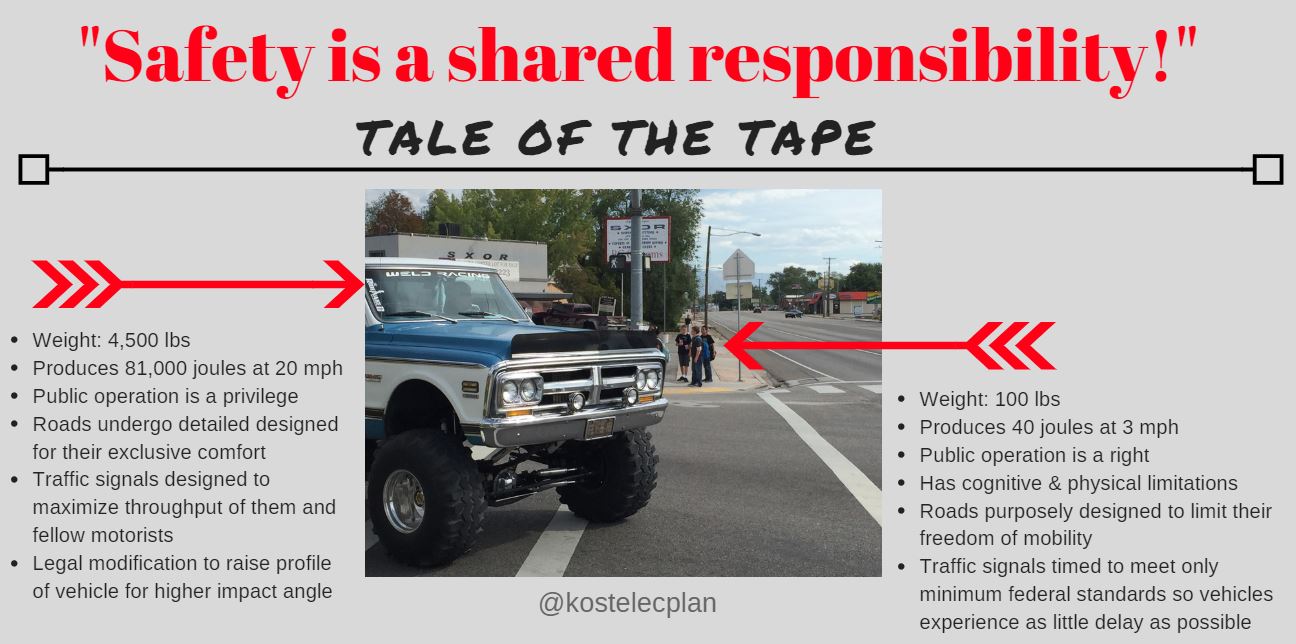

On the 4th day of Safety Myths, my DOT gave to me…Shared responsibility!