The 12 Days of Safety Myths

December 18, 2018

By Don Kostelec

The Safety House has so many lights strung upon it that it puts Clark Griswold’s abode to shame.

Context Sensitive Solutions. Complete Streets Policy. Active Transportation Plans. Corridor Studies. Environmental Justice. Heads Up. Vision Zero.

When we try to plug them into our communities, the results are the same as Clark’s: A massive build-up, great presentations, heightened expectations, drumroll, please…DRUMROLL…

Doink.

I’m tired of the false promises. I’m tired of being strung along by the engineering profession, telling us that whatever their latest wave of buzzword practices will be finally be the solution that leads to safer streets for all road users.

The buzzwords seem to evolve but the actual engineering of streets doesn’t. In my nearly 18 years in this profession I feel like we’ve been exposed to three major phases of false promises.

Context Sensitive Solutions

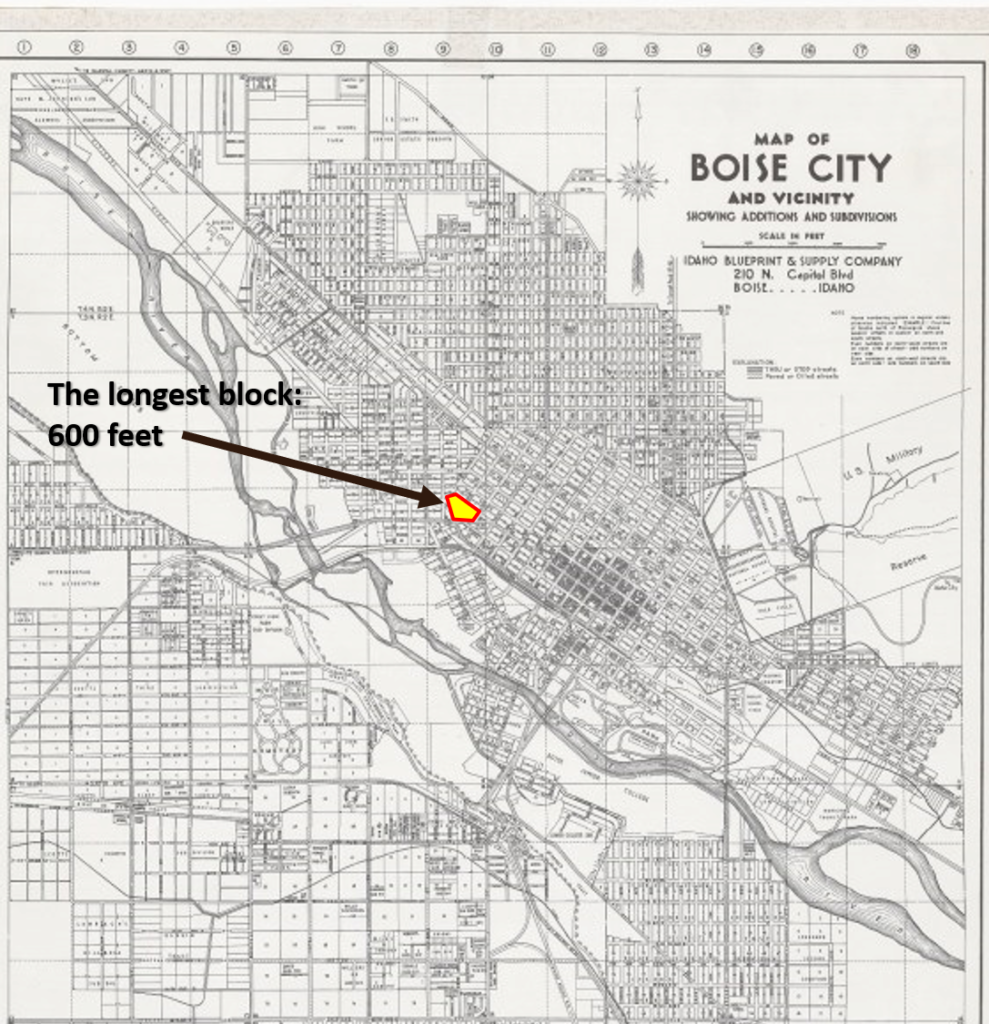

This was the rage in the late 1990s and early 2000s. On the heels of major federal transportation legislation in the early 1990s, FHWA published its Flexibility in Highway Design manual in 1997. It states on page 15, Considering Scale:

- “People driving in a car see the world at a much different scale than people walking on the street… In many road designs, pedestrian needs were considered only after the needs of motorized vehicles. Not only does this make for unsafe conditions for pedestrians, it can also drastically change how a roadway corridor is used. Widening a roadway that once allowed pedestrian access to the two sides of the street can turn the roadway into a barrier and change the way pedestrians use the road and its edges.”

That was 21 years ago. They recognized the engineering process was predicated on first identifying and laying out the road for all the comfort needs of a motorist: Detailed vehicle level of service analysis, 85th percentile speed analysis, number of lanes, turning radii, etc. If a community was lucky enough to have sidewalks or bike lanes included, those features were last in line in the design process and simply slapped alongside the primary features for motorists. There was no integration of how the needs of people who walk or bike were influenced beyond the presence or absence of their own five-feet of space alongside the road.

Assessing the character or context of an area, both its human and natural environment, was identified as a key component to transportation engineering through that FHWA guide. It was meant to change the design paradigm and make the needs of not only active transportation users, but other facets of the environment, an input to the design and something that drove an authentic evaluation of the tradeoffs.

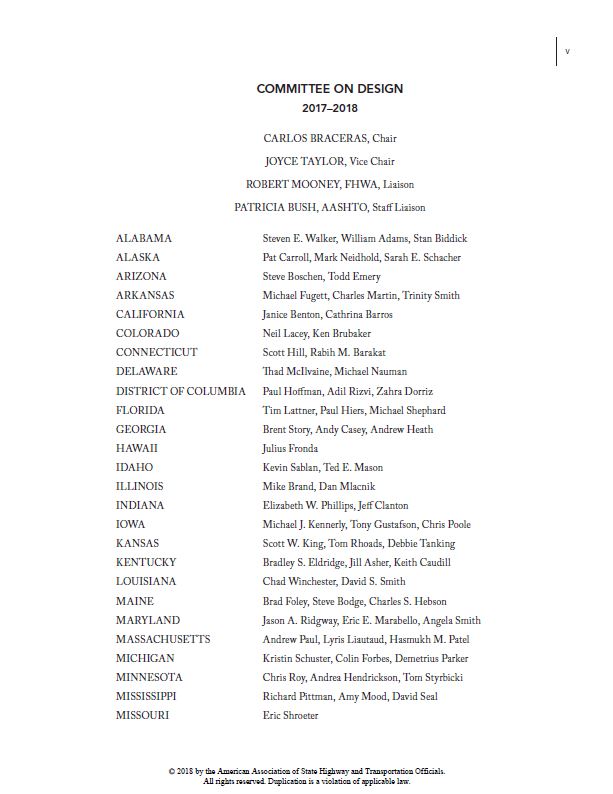

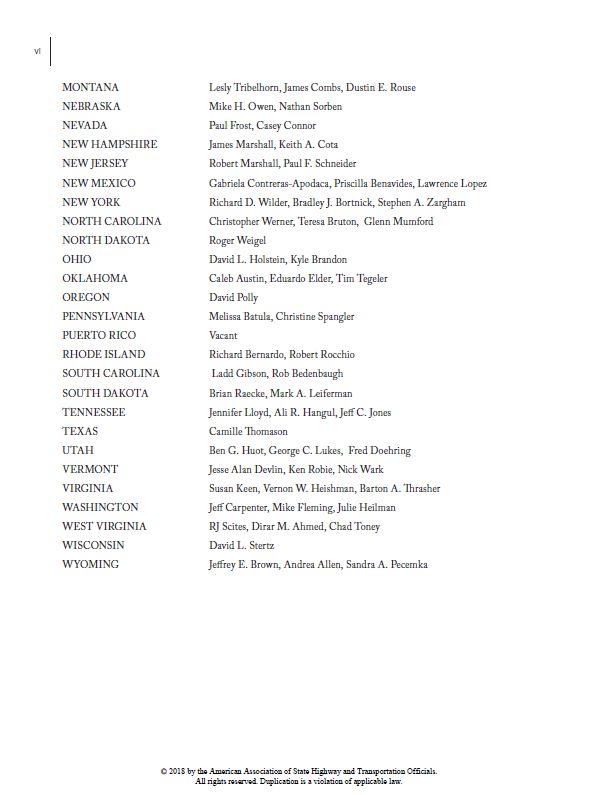

This spawned the Context Sensitive Solutions (CSS) movement. In 2004, the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials published A Guide for Achieving Flexibility in Highway Design in response to CSS and building upon FHWA’s initial flexibility guide.

The introduction of AASHTO’s flexibility guide states:

- “Context sensitive solutions (CSS)…recognizes that a transportation facility, by the way it is integrated with the community, can have far-reaching impacts (positive and negative) beyond its traffic or transportation function.”

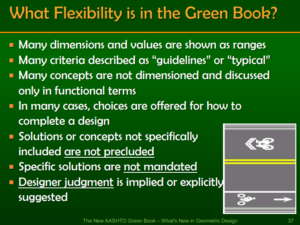

The AASHTO flexibility guide has some striking statements that contradict assertions you still commonly hear from traffic engineers and other transportation professionals:

- Level of Service: AASHTO’s vehicle level of service measures “are for guidance only. Failure to achieve a level of service indicated in (AASHTO’s LOS table) does not constitute of a non-standard design decision.” (page 13)

- Design Speed: “Given the historic equating of design speed with design quality, the notion of designing a high-quality, low speed road is counter-intuitive to some highway engineers…Context-sensitive solutions for the urban environment often involve creating a safe roadway environment in which the driver is encouraged by the roadway’s features and the surrounding area to operate a low speeds.” (page 19). Today we call that “target speed.”

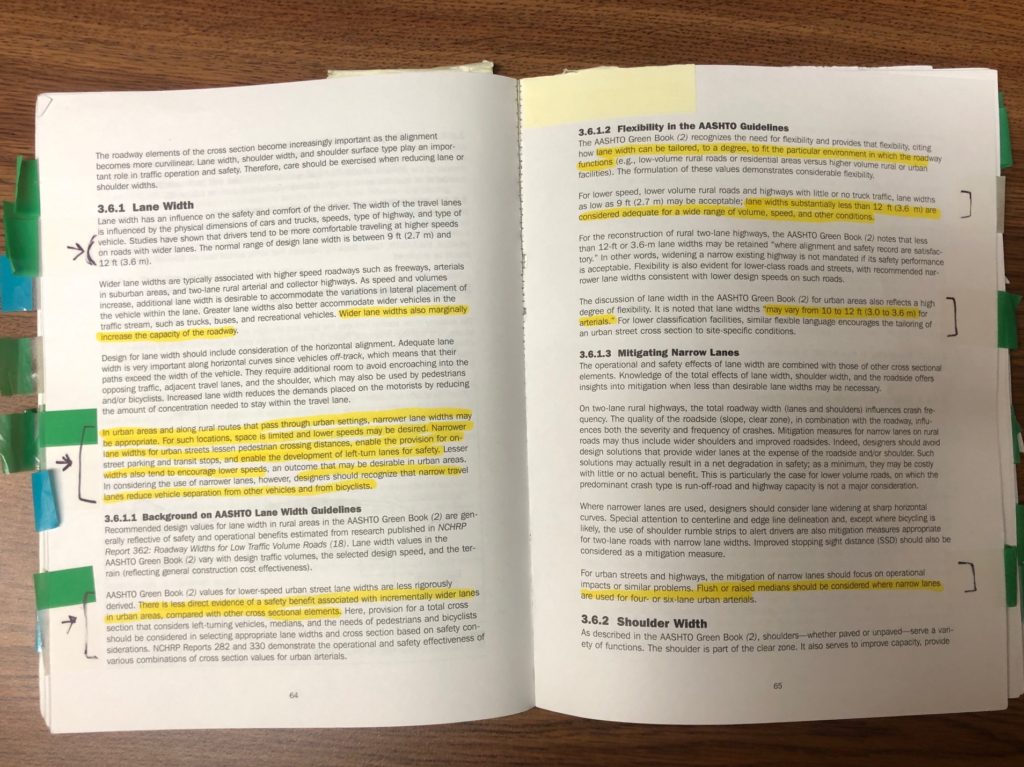

- Lane Widths: “In urban areas…narrower lane widths may be appropriate. Narrower lane widths lessen pedestrian crossing distances…and…also tend to encourage lower speeds…There is less direct evidence of a safety benefit associated with incrementally wider lanes in urban areas. It is noted that lane widths may vary from 10 to 12 ft for arterials.” (pages 64-65)

- Liability: “In order to reduce exposure to losses due to liability claims, it is essential that the planning and design process be thoroughly documented. If a new or innovative solution is proposed, reference to where it has been applied, how it has performed, and how the circumstances are similar…would be good information to include in project reports…Note that this requirement is really no different from best current practices.” (page 107)

The AASHTO flexibility guide served as the foundation for what at the time was the most meaningful project of my career: The Ada County Highway District’s Transportation & Land Use Integration Plan. It was a $1 million effort I led in 2006 and 2007 with a goal of changing the way the agency conducted its business with regard to project design. If we tried it today, we would probably call it a Vision Zero plan.

We bought 40 copies of AASHTO’s flexibility guide to give to department managers, planners, and engineers. When it was clear the agency didn’t want to change its practices, I left the agency and the Boise region.

At my going away party, my boss, who was equally frustrated at the agency’s stubbornness, handed me a copy of the AASHTO flexibility guide and said to me, “Take this with you. I know the other copies won’t be used here.”

Complete Streets

Despite all the Context Sensitive Solutions guidance from FHWA and AASHTO clearly justifying safer design considerations for vulnerable road users, it didn’t really change anything. It was just another bucket of coal from Santa Claus, PE.

Enter the Complete Streets movement. As much as the FHWA and AASHTO flexibility guidance justified a change in perspective, it was realized that state and local agencies still had to adopt their own design and funding policies and that some agencies took federal guidance and proceed to adopt facets of it as more stringent local design standards or policies than the federal guidance suggested.

I departed Boise and moved back to my home state of North Carolina in early 2008 to take a job in private consulting. I knew at that time North Carolina’s DOT had a pretty good reputation for Context Sensitive Solutions.

At least that’s what I thought based on tens of thousands of dollars NCDOT spent sending their staff to give presentations about it at national conferences. They bragged about trained more than 1,500 of NCDOT’s designers and project decision-makers on CSS. I think it’s safe to say they spent more sending people to those conferences and training them than they spent implementing it.

In July 2009, the NCDOT Board of Directors adopted what was called a “Complete Streets policy.” We were all duped into thinking this would somehow change the organization and make those CSS concepts more applicable to active transportation needs.

It was held up by national organizations as a model for others to embrace and implement. The National Complete Streets Coalition, now Smart Growth America, said, “The National Complete Streets Coalition applauds the NCDOT for taking this step and looks forward the many great projects sure to come out of the new policy.”

#LOL #ROFLMAO

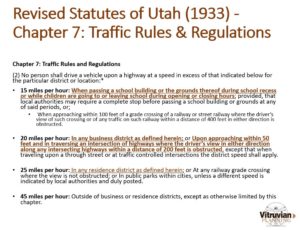

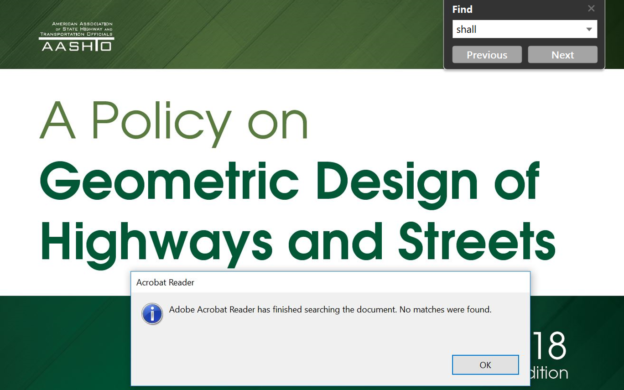

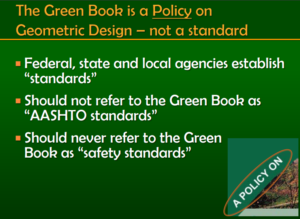

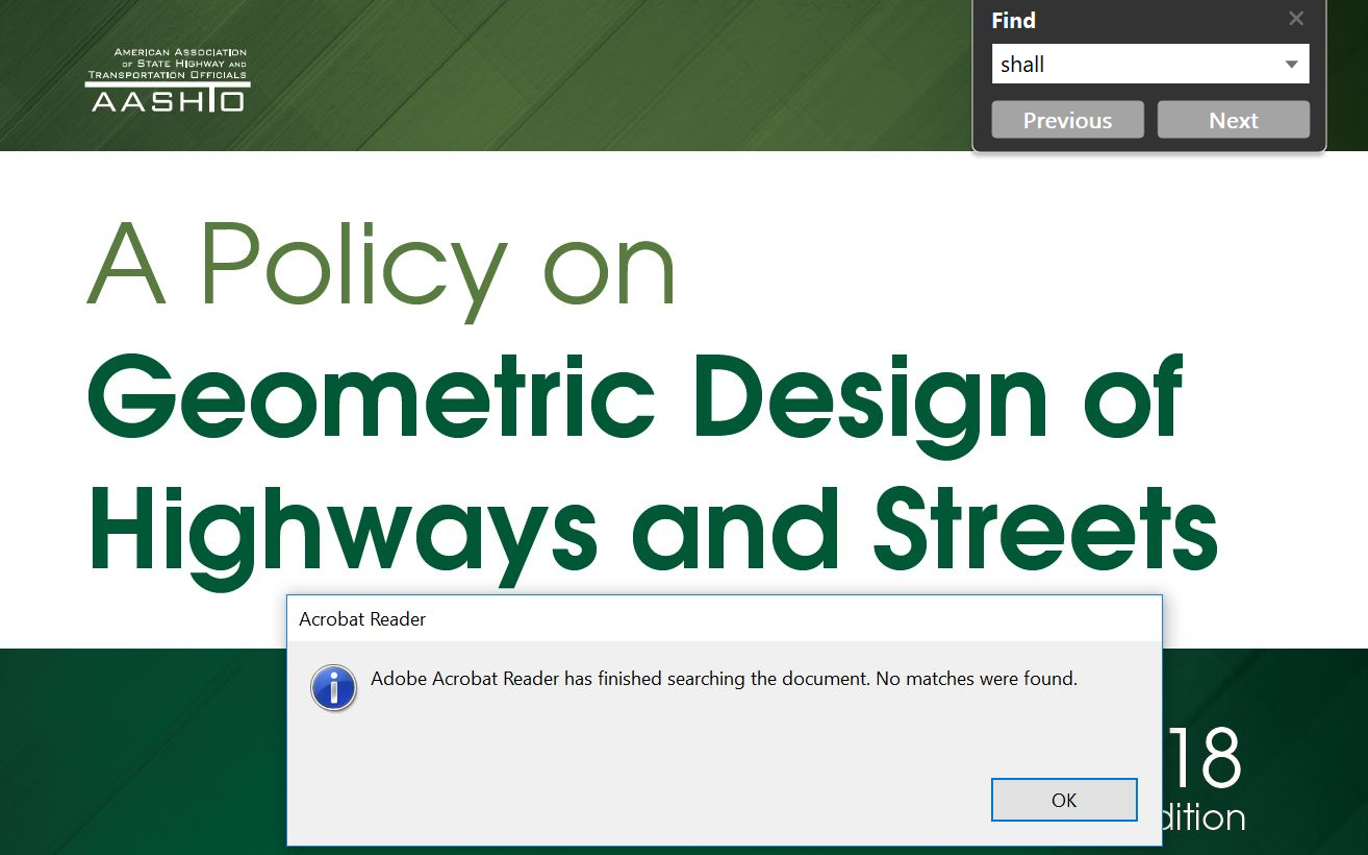

It turns out that what NCDOT called a “policy” was really nothing more than a resolution, a declaration of the Board of Transportation. The “policy” contained no compulsory statement for NCDOT engineers to follow; no “shall” or “must” statements. It made no commitment to fund implementation of the policy.

I could write 10,000 words on the debacle of NCDOT’s Complete Streets policy. Streetsblog summed it up nicely after it reviewed a 2018 NCDOT report stating that nearly 10 years after its adoption, the application of Complete Streets within NCDOT was non-existent. The report states:

- “…the policy is written more as an advisory document and does not include enforcement measures and language needed for implementation. A sentiment echoed in multiple external interviews was that Complete Streets elements are typically viewed as an enhancement, as opposed to a necessary component, of a project.” (page 8 of the PDF file)

- NCDOT staff interviewed for the report said the “rarely, if ever,consult the Complete Streets Design and Planning Guidelines for design standards.”

The result in North Carolina since NCDOT passed its Complete Streets policy: Rates of pedestrian and bicyclist deaths have increased dramatically and NCDOT’s lack of implementation of its policy led to more than two, full five-year cycles of Statewide Transportation Improvement Program projects lacking safe engineering for vulnerable road users.

North Carolina’s story isn’t much different than what we are seeing in many other state and local agencies: So-called Complete Streets “policies” are mostly resolutions, not ordinances, that contain few if any compulsory clauses or dedication of funding.

Just another bucket of coal left under the tree.

Vision Zero

I’m this/close to giving up on Vision Zero in the United States. I feel that way because the term has already been bastardized by the traffic safety offices of state DOTs.

Elected officials and the public are confused when you try to bring up what real Vision Zero means. They think it’s a traffic safety education campaign sprinkled with some focused law enforcement. They are socially engineered by state DOTs to think that way.

Road to Zero. Toward Zero Deaths. This is how national organizations like the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration and its partners have diluted Vision Zero before it ever had a chance to emerge. They still seem to insist that perfecting human behavior will get us to zero traffic deaths.

An Alaska DOT engineer, when I brought up the topic at a 2017 conference, challenged me when I said Vision Zero was a design-focused endeavor. He asserted it was based on education and enforcement. My response was this: “Engineering influences 100% of a road’s users 100% of the time. Education and enforcement may not reach any of a road’s users and those efforts, even when well-funded, are sporadic at best.”

The state DOT twitter handles for Zero-whatever-they-want-to-call-it reflect their lack of perspective. Explore them a little bit.

- Utah DOT: @ZeroFatalities

- Iowa DOT: @ZeroIowa

- Nevada DOT: @DriveSafeNV

- North Carolina DOT: @NCVisionZero

Those of you in San Francisco or New York City or Boston or Portland or Seattle may disagree. There are certainly some aspects of what those cities are doing that reflect a true safe systems approach to Vision Zero. They take engineering seriously on many accounts. I wish they were the national model and the national voice through AASHTO, NHTSA, and FHWA. My only real hope is the Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE). They are partnering with the Vision Zero Network and the speed management class they led at the Vision Zero Cities conference was outstanding.

The problem for the rest of the country is so many small- and medium-sized cities look to their state DOT for guidance, policy, and design standards. “They’re the experts, so let’s do what they do.” The smaller cities don’t have the budgets to develop their own methods for properly incorporating a Vision Zero approach to engineering. They take whatever the state DOT feeds them. Many even recruit state DOT lifers to come finish out their careers within a city transportation department.

I’ll reserve final judgment for a couple more years. For 18 years I’ve waited for the right DOT to flip the right switch to light the way.

Hurry it up, Clark. I’m freezing my baguettes off.

Previous Posts in the 12 Days of Safety Myths Series